Theresa and I travel all over rural Arkansas looking for new stories to post on DownHomeArkansas.net. One of our most recent outings took us to the small Boone County community of Everton where we rented a remote cabin for some weekend relaxation.

Neither of us had ever heard of Everton, population 104. It’s located on Highway 206 just a short drive southeast of Harrison. But unless you happened to be driving off Highway 65 to Eros or Bruno or Olvey, chances are good you’ve never passed through it. It had escaped our notice, even though we make a habit of driving off the beaten path to neat places like this. So, after checking into our Airbnb, we drove around town to see what we might see.

Lots of historic buildings still stand in Everton, including an old bank and a once-beautiful hotel. There are several churches, a really nice city park, a very new fire station (watch for an upcoming blog about that) and a modern community center designed to resemble a railroad depot.

As we drove around the town, though, what really grabbed our attention was the mention of a corn cob pipe factory Theresa found while doing research on the internet. We didn’t know that such places even existed and quickly agreed this was just the type of story we wanted to share on DownHome Arkansas. Here’s what we learned.

The Rise of the Corn Cob Pipe Factory

In the early 20th century, the corn cob pipe industry was flourishing across the United States. Who knew, right? These pipes, known for their simplicity and affordability, became a popular choice among smokers. Everton, with its abundant cornfields and strategic location along the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad, emerged as an ideal location for a corn cob pipe factory. The establishment of this factory brought jobs and economic growth to the small community, offering employment opportunities to many local residents.

The factory, known as the Uncle Sam Cob Pipe Works, was founded by an enterprising Italian immigrant from New York City named Joe Migliore. After a fateful visit to Everton in 1915, Migliore returned years later, married a local woman named Willie Greenhaw and purchased a farm where he began producing corn cob pipes. The factory quickly became a significant part of Everton’s identity, producing thousands of pipes daily at its peak.

The Craftsmanship Behind Corn Cob Pipes

The process of making corn cob pipes was both an art and a science. The cobs, primarily sourced from local farms, underwent a meticulous process of drying, curing and shaping. Skilled craftsmen fashioned these cobs into durable and functional smoking pipes. Each pipe was unique, reflecting the quality and care put into its creation. The simplicity of the design belied the expertise required to produce a pipe that was both aesthetically pleasing and functional.

Migliore was innovative in his approach, experimenting with a cross between St. Charles White and Boone County White corn to produce the large cobs necessary for his pipes. The craftsmanship extended beyond the pipes themselves, with Migliore introducing new hickory pipe designs and even venturing into the production of kitchen utensils.

Production and Workforce

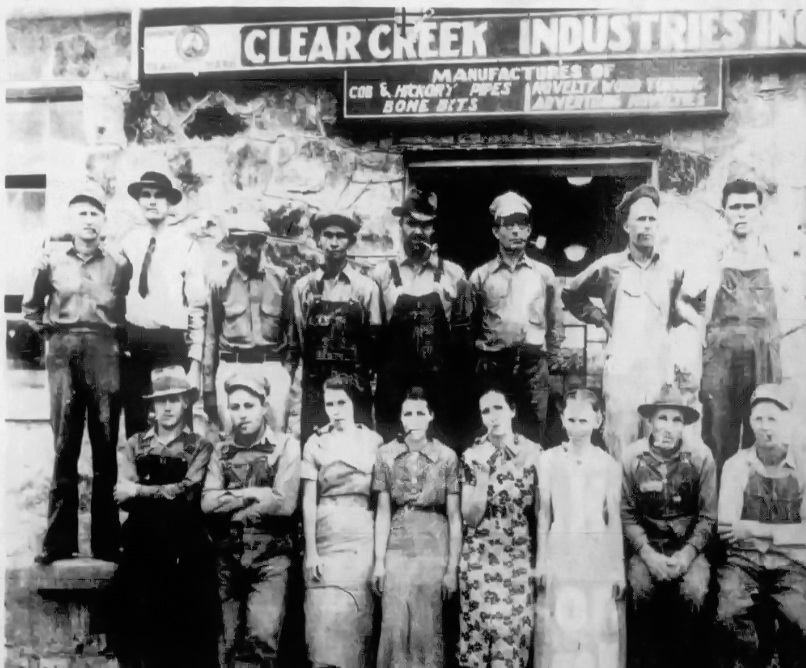

The Everton corn cob pipe factory was a bustling center of activity. Historical records and local accounts suggest that the factory produced between 500 to 1,000 pipes per day, translating to an annual output of approximately 150,000 to 300,000 pipes. At its peak, the factory employed 15 full-time workers, expanding to 45 during rush periods.

The factory’s workers were deeply invested in their craft. From the meticulous drying of corn cobs to the shaping of pipes and the creation of bone and rubber bits for mouthpieces, every stage of production required skill and dedication. The factory’s equipment, much of it custom-made, reflected the innovative spirit of Migliore and his team.

Impact on the Local Economy

For many years, the corn cob pipe factory was a cornerstone of Everton’s economy. It provided stable employment and supported numerous families in the area. The factory’s presence fostered a sense of community, with many residents taking pride in their contributions to the production of these iconic smoking accessories. Local businesses benefited from the influx of workers, and the town experienced a period of economic stability and growth.

During the Great Depression, the factory faced significant challenges, but Migliore’s resourcefulness kept it afloat. He ensured farmers were compensated fairly for their cobs, provided special corn seeds and even allowed customers discounts for prompt payment. These efforts helped the factory survive the tough economic times.

The Decline of the Industry

Despite its success, the Everton corn cob pipe factory faced challenges as the 20th century progressed. Changes in smoking habits, competition from other materials and the rise of mass production techniques led to a decline in demand for traditional corn cob pipes. The onset of World War II further strained the factory as essential materials became scarce and competition from foreign manufacturers increased. By 1942, the factory could no longer sustain its operations and had to close its doors. The closure marked the end of an era for Everton, leaving behind memories of a once-thriving industry.

Preserving the Legacy

Today, the story of the Everton corn cob pipe factory is preserved through local history enthusiasts and the collective memory of the town’s older residents. If the old factory building still stands, Theresa and I could not find it. But the legacy of the corn cob pipe industry remains a point of pride for Everton. Efforts to document and share this history help keep the memory alive for future generations.

The factory’s founder, Joe Migliore, passed away in 1956, but his impact on Everton and the broader world of corn cob pipes continues to be felt. Noted figures such as General Douglas MacArthur and New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia were among those who smoked Uncle Sam pipes, and the factory’s products were sold worldwide, including in Migliore’s native Italy.

Conclusion

The corn cob pipe factory in Everton, Arkansas, was more than just a place of employment; it was a symbol of the town’s resilience and ingenuity. Though the factory no longer operates, its impact on the community and the memories it created continue to be cherished.

As we look back on this chapter of Everton’s history, we are reminded of the importance of preserving stories like this that shape our Arkansas heritage. The legacy of the Uncle Sam Cob Pipe Works stands as a testament to the enduring spirit of a small Arkansas town and the people who made it thrive.

Keith “Catfish” Sutton of Alexander, Arkansas, is one of the country’s best-known outdoor

journalists. His stories and photographs about fishing, hunting, wildlife and conservation have

been read by millions in hundreds of books, magazines, newspapers and websites. He and his

wife Theresa own C&C Outdoor Productions Inc., an Arkansas-based writing, photography,

lecturing and editorial service.

Get DownHome Arkansas blog posts, news, and more directly by email. Give us your name and email if you’d like to subscribe.